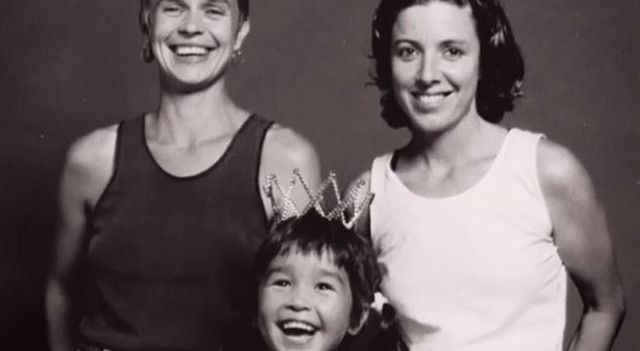

Maya Newell writes about growing up a “gayby” with two lesbian mothers.

When I was seven, my mother Liz and I walked into the local butcher’s shop to buy some offcuts for the dog. It was the only reason we ever visited the butcher’s as my other mother, Donna, was (stereotypically) a raging vegetarian. Liz leaned over the counter and said, “Just a kilo of chicken wings for the dog,” to which the butcher, a big, meaty man, replied, “Guess your husband ain’t getting lucky tonight. Do you want to get him some chops with that?”

When I was seven, my mother Liz and I walked into the local butcher’s shop to buy some offcuts for the dog. It was the only reason we ever visited the butcher’s as my other mother, Donna, was (stereotypically) a raging vegetarian. Liz leaned over the counter and said, “Just a kilo of chicken wings for the dog,” to which the butcher, a big, meaty man, replied, “Guess your husband ain’t getting lucky tonight. Do you want to get him some chops with that?”

On this particular day, Liz was in no mood to have that particular conversation with this particular man, so she casually replied, “No, he doesn’t eat much meat.”

She walked out of the shop as if nothing had happened. I looked up at her, confused, and said, “Why did you lie? Why did you say that Donna is a man?” Liz paused for a long time.

“Darling, I am so sorry. You have two mums, but sometimes you can choose to tell people and sometimes you don’t have to.” That’s when I came to the uncomfortable realisation that there are some people in the world who might not approve of my family.

Now that I am older, I understand – like my mother – that not every moment calls for the “out and proud” approach. Sometimes you just don’t feel like pouring your story out and fighting for the gay liberation movement, one person at a time.

At primary school, it was easy. I bragged about having an extra mum and many of my friends wished they could ride wearing sparkles in the lead float of the Mardi Gras Parade with us. Everyone had seen Liz and Donna picking me up and coming into the classroom, whereas in high school I suddenly had a secret. With NSW upper house MP Fred Nile, leader of the Christian Democrats, and other politicians blaring homophobic rhetoric, I had reason to believe that at least a few students might give me a hard time.

So in my first term, I sat biting my nails next to my new group of friends. “I have something to tell you,” I said one day in a voice that demanded attention. Anna, Victoria, Caitlin and a few other girls turned to face me. I blurted, “I have lesbian mums.” Everyone went silent, and then Anna offered, “That’s cool, I have a gay uncle.”

A sea of stories swamped me. Everyone told me some roundabout connection they had with gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgender people. (This is actually the usual response: people want you to feel that it is okay by them, which is reassuring.)

It’s not always like this, though. There was the taxi driver who made me get out of his cab, and the priest who told me there was still a chance I might be able to save my soul if I never spoke to my mothers again.

I had never missed not having a father, never felt a need for a connection with the man who had helped to make me, but the constant onslaught of questions from worried strangers concerning my lack of a “daddy” made me acutely aware that perhaps I should want one, or miss one, even if only a little bit. These dads must be pretty good if everyone’s asking so much about them.

When my mothers conceived me, reproductive technology was not legally available to lesbians in Australia. This was the 1980s. So they asked a friend in Japan if he would like to help them, and he said yes. Japan was far enough away that there was no threat of him coming unannounced to claim parental rights (which happened to many lesbians without the law to protect their arrangements), and Liz had grown up in Japan and so had a close connection to the country. Most years, Liz and Donna would send him a Christmas card with an updated photo of the results of his donation.

While most kids are grappling with a basic understanding of “the birds and the bees”, many gaybies are already fluent in the language of IVF and assisted reproductive technology, not to mention the many uses of turkey basters. And some of us have butch mums or camp dads and thus have an understanding of the fluidity of gender – that both mums and dads can love football, do the cooking, knit jumpers and make sure the kids are safe.

We have donor fathers or surrogate mothers and some of us might even have donor siblings we’ll meet one day, which makes for demands that children from hetero couples don’t have, like getting extra creative on Mother’s Day and Father’s Day.

Gaybies sometimes see the ugliness of sexual discrimination, and growing up in a diverse family means many kids have embedded in them an openness to all kinds of difference.

For my documentary Growing Up Gayby, I interviewed Fred Nile about his anti-gay views. Over a cup of English breakfast tea I listened as he talked about his life.

I heard about how both his mother and his father grew up as orphans, deserted by their parents, and how they were moved from one foster home to another. I heard about how hard his mother struggled to maintain a “normal” family after her own was broken, and about the challenges of migrating to Australia. They did it tough, there’s no denying.

I wanted to be angry at this man who had fuelled so much hatred towards my family, but I found myself genuinely interested. All the clues as to how and why a man could believe so unwaveringly in the promise of the traditional family unit became clear to me.

I understood a little better because I opened myself to his story. It is my hope that my story might do the same for him, and others who have been too quick to judge.

Despite the love, satisfaction and pride that comes with parenting, it is one of the hardest things a person or a couple will endure. I wish it was as simple as man + woman = well-adjusted child. But in my opinion there is much more at work, and parents being of opposite gender is the least significant factor in the raising of a child.

Maya Newell is the director of the documentary Growing Up Gayby, to air on ABC2 on November 20.

Photo: Sahlan Hayes

Author: The Age

Publication: The Age

Date: 17 November 2013

Read the original article here